Follow the Data Podcast: Greenwood Art Project Builds on History of Black Wall Street in Tulsa, OK

In part two of a two part episode, Hannibal Johnson and Rick Lowe, discuss the future of Tulsa, Oklahoma in historical context, along with the potential impact of the Greenwood Art Project. Tulsa is the winner of Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Public Art Challenge. The Greenwood Art Project commemorates the 100th anniversary of the destruction of a thriving black community in Tulsa known as Black Wall Street. The project celebrates the resilience and recovery of the community.

Hannibal Johnson is an author, attorney, professor and consultant. He is an expert on the African-American experience in Oklahoma and its broader historic impact on American history. Rick Lowe is an artist, best known for Project Row Houses, which he started in Houston in 1993. He has worked with communities and exhibited all over the world. Stephanie Dockery of the Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Arts team moderates a conversation with Johnson and Lowe.

Listen to Part 1 of the episode by subscribing to Follow the Data – and read more from Rick Lowe here.

You can hear the podcast and past episodes in the following ways:

- Check us out on Spotify

- Listen to the episode and follow us on SoundCloud

- Follow the Data is also available on Stitcher – be sure to rate and review each episode!

After listening to this podcast, learn more in a Q&A with Rick Lowe: Honoring the Past and Shaping the Future through Public Art.

We hope you enjoy this episode. Follow us on Twitter @BloombergDotOrg for information about our next episode.

Until then, keep following the data!

FULL TRANSCRIPT

KATHERINE OLIVER: Welcome to Follow the Data, I’m your host, Katherine Oliver. This is episode is the second part of a two part feature on the winner of the Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Public Art Challenge. The Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Arts Program seeks to support innovative temporary public art projects that enhance the quality of life in cities. The Public Art Challenge encourages mayors to collaborate with artists to develop projects that address community issues.

As the winner of the challenge, Tulsa, Oklahoma will receive one million dollars for the Greenwood Art Project, a group of temporary public artworks which commemorate the 100th anniversary of the destruction of a thriving black community in Tulsa known as Black Wall Street. The project celebrates the resilience and recovery of the community. Kate Levin, Bloomberg Philanthropies’ arts program lead introduces two speakers intimately involved in the development of the Greenwood Art Project, Hannibal Johnson and Rick Lowe.

In the first part of this feature, Johnson discusses the history of Tulsa and Black Wall Street and Lowe speaks to the development of the Greenwood Art Project. Listen to part one by subscribing to Follow the Data podcast and reviewing past episodes.

In this episode, Hannibal and Johnson address the future of the project, and Stephanie Dockery of the Bloomberg Philanthropies’ arts team moderates a discussion about how the project was selected to win the Public Art Challenge.

Listen to the episode now.

KATE LEVIN: Good morning, everyone. Welcome to our conversation with some extraordinary guests about the Tulsa Public Art Challenge Project, which centers around a key episode in U.S. history that is far too little known. The Public Art Challenge is our grant program which offers up to $1 million to U.S. cities for temporary public art projects that address a significant civic issue.

And the initiative really reflects Mike’s experience as mayor, during which time we did close to 500 public art projects. And while they were all different in form, in location, in type, they all had the same kind of virtuous circle of bringing together entities that don’t normally function well together and sometimes don’t function at all. Stakeholders, neighbors, city agencies, sometimes state and federal agencies, local businesses, funders all of them collaborated around these projects in uniquely beneficial ways.

So, in 2014, we launched the first Public Art Challenge and supported four projects across six cities, and we announced a second round last year. And we’re honored to be supporting five new projects over the two-year grant cycle. And, of course, my amazing colleagues, Anita Contini and Stephanie Dockery oversee those projects. So, we’re so pleased to have two key proponents with us today. Hannibal Johnson is an author, an attorney, a professor, and a consultant specializing in several fields including diversity and inclusion, and nonprofit leadership and management.

And he has written a number of influential books that chronicle the African-American experience in Oklahoma and its uniquely impactful role in American history. He’s also a successful playwright, and has received numerous honors and recognitions for his work.

And Rick Lowe is a Houston-based artist who has worked with communities and exhibited all over the world. Some of us had the pleasure of seeing his work as part of Documenta 14 last summer in Athens, which is one of the Bloomberg Associates cities, and he has been a real inspiration for the Associates work that we are doing in Houston. He is best known for Project Row Houses, which he started in Houston in 1993, he is a MacArthur Fellow who has also served on the National Council on the Arts.

So, Hannibal and Rick are each going to talk to us a little bit about their journeys, and then Stephanie is going to moderate a conversation between them. Thanks so much.

HANNIBAL JOHNSON: So, my task this morning is to give you a quick overview of the history of Tulsa’s historic Greenwood District, the traditional African-American community in Tulsa known primarily for two things. One, as the hub of black entrepreneurial activity in the early part of the 20th century, and secondly, as the site of the worst of the so-called race riots that happened in America.

I’m going to talk about discrete chapters in this larger narrative. The overarching theme of this narrative for me is the human spirit. It’s fundamentally about people who had vision, people who were determined, and people who ultimately were resilient after the utter devastation of their community. So, I’m going to divide the talk into chapters: regeneration, which talks about the remarkable rebuilding shortly after the devastation in 1921; and renaissance, which talks a little bit about some of the current developments in the Greenwood community.

What caused the 1921 Tulsa race riot? The systemic institutional racism that existed throughout the United States generally is a cause. Land lust. The Greenwood district, the historic African-American community in Tulsa abuts downtown separated by the Frisco tracks, literally separated by the railroad tracks. So, that land was desirable by the railroads and by a number of other corporate interests. Jealousy. African-Americans were supposed to be inferior to whites, if not subhuman, during this period. That was a prevalent thought process during this period.

So, jealousy was certainly one of the causes. In Tulsa, there are a couple of somewhat unique elements. The KKK, the Klan, formed in Oklahoma in the early 1920s and really blossomed or burgeoned throughout the ’20s, peaking in the very late 1920s. So, the Klan had a presence in Tulsa early on. The other thing that happened in Tulsa was the media helped fan the flames of racial unrest. A particular media outlet called the Tulsa Tribune, which is the daily afternoon newspaper, published a series of inflammatory articles and editorials that really got the community up in arms.

So, we’re sitting on this tinderbox and we only need a match to be thrown on it. And that match was a trigger incident involving two teenagers, Dick Rowland, a black 19-year-old Tucson boy, Sarah Page, a white girl who operated an elevator in a downtown building. Dick Rowland needed to use the restroom. Facilities were segregated. He knew that there was a place in the Drexel Building where Sarah Page was working. He went to the Drexel building, boarded the elevator. Something happened, we don’t know exactly what, but the elevator kind of lurched and caused Dick Rowland to bump into Sarah Paige. She began to scream. The elevator came back down to the lobby. Both of them exited the elevator. There was a clerk from a nearby store who came to Sarah Page’s assistance. Again, she was hysterical, and The Tribune, this newspaper, published the story the next day.

Mind you, Sarah Page would never testify against Dick Rowland because nothing ever happened, but the Tribune published a story the next day that said that this black boy had attempted to rape this respected white girl in a public space in broad daylight in a downtown Tulsa building. That got the community up in arms. Dick Rowland was arrested, taken to the jail, which is on the top floor of the courthouse. A large white mob began to gather, threatening to lynch Dick Rowland.

Black men came to the courthouse to protect Dick Rowland because they were really concerned about his safety, his very life. There was an exchange of words between the smaller black group and the larger white group. There was a struggle over a gun that one of the black man had, the gun discharged, and things went south from there.

Now, as a result of this incident, we know that somewhere between 100 and 300 people lost their lives, at least 1,250 structures, including homes and businesses, were destroyed, property damage conservatively estimated ranges from $1.5 to $2 million dollars, which in today’s money would be in excess of $20 million dollars. The Red Cross provided relief. Many black families spent days, weeks, and months living in tent cities throughout the city. Black men and, to some extent, to a lesser extent, women and children were interned, very much like people of Japanese ancestry were interned during World War II. They’re taken to these encampments and to get out, they had to have a green card, literally a green card countersigned by a white person to get out of these encampments.

This is in Tulsa in 1921. The good news is, again, about the character of these people who said essentially, we shall not be moved. So, even after this devastation, many African-Americans decided to remain and to rebuild. The city put up all manner of obstacles, including changing the fire code to make it more difficult to rebuild, and rezoning the Greenwood area. Those measures were successfully fought by B.C. Franklin, who was the father of the eminent historian, Dr. John Hope Franklin. And the community was able to rebuild and rebound sufficient in four years to host the national conference of the National Negro Business League, which is Booker T. Washington’s black Chamber of Commerce.

That meeting was held in Tulsa 1925. The peak of this community is it about 1942, when there are more than 200 black-owned and black-operated businesses back on Greenwood. So, the community came back bigger and better than ever as an entrepreneurial enclave after this remarkable devastation in 1921. So, today in Greenwood, we have kind of an amalgam of cultural, educational, residential, commercial, and entertainment interests, and it’s a community that really is struggling with its identity and with its branding. I think Rick will probably address that, to some extent. So, what happened between the peak of the community and where we are today?

A number of things happened, the most ironic of which, I think, is integration. Now, I certainly embrace integration as a positive value, but if you think about why the Greenwood community existed as a business community in the first instance, it is because of segregation. It was a community of necessity. And when integration comes along and people are able to spend money outside, get more things at lower cost, money flows out without commensurate dollars flowing back in. It undermines the financial foundation of the community. The other dynamic that helped the decline of the community was urban renewal. A lot of people in Tulsa call it urban removal because there is a highway, 244, that bisects what was the heart of the Greenwood community.

Other things that really help speed along the decline of the community include the change in the economy. The Greenwood community really was more of a black Main Street than a black Wall Street. These are small businesses, mom and pop operations, and so forth. And so again, there was no mentorship process in place. So, when the original owners began to die, to move, et cetera, the businesses tended to fold. So, we are where we are in Greenwood today with this collection of kind of odd entities struggling for identity. And with that, I’ll cede that to Rick.

RICK LOWE: It’s so great to hear Hannibal speak about it because I was introduced to the depth of the Greenwood story through Hannibal’s book, “Black Wall Street.” Now, I’m going briefly just say, there’s not a lot for me to say about the Greenwood Art Project at this point because we’re in the very early stages. Just to contextualize this for folks.

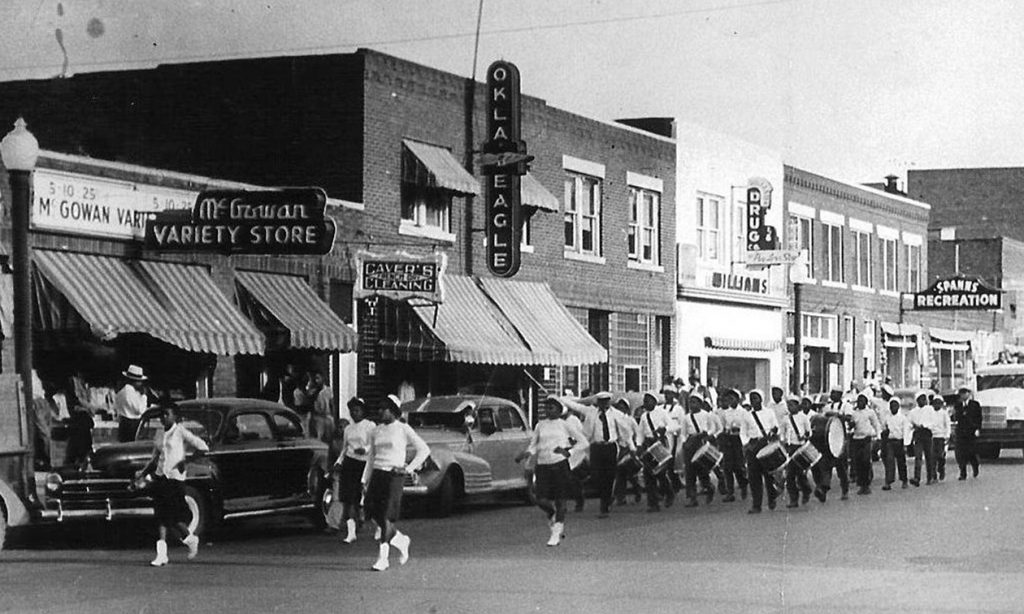

When I first was introduced to this, Greenwood and then the subtitle Black Wall Street, of course you start thinking about Wall Street, right? And what does Wall Street mean? Wall Street represents the economic health of our nation, right? And so, I was looking at images and thinking about how we talk about Wall Street, it’s about money. It’s about big money, it’s bullish. It’s about power. It’s a major power thing. When I started to look into the Black Wall Street thing, it was like ah, there’s a lot more humility about this notion of Black Wall Street.

As Hannibal said, it was much more a Black Main Street than Black Wall Street. This came about not because of some notion of excess and the kind of power that that Wall Street represents. It was about survival. How do people pull together economically to sustain themselves? That begins to be the story of Greenwood and how it came about.

For those who do know about Black Wall Street, they know about it from the standpoint, the Tulsa riots, they know about it from the standpoint of the destruction, the terrorizing. But they don’t know about it from the standpoint of, as Hannibal said, the people came together to rebuild this place. What I find really interesting about that, if you Google the Tulsa riots, or Black Wall Street Tulsa and that kind of stuff, it’s hard to find images of the vibrancy of that culture, the business district there. As Hannibal said, Highway 244 moved through and it just sliced part of the neighborhood off. They turned whole northern part of it into a university park, basically getting rid of the street grid. There’s actually a baseball stadium that’s just behind little houses –the one block where the houses still remain. How do we deal with this notion of honoring the past this neighborhood, but also positioning it in a place that it could go forward into the future.

One young woman I met, with we were talking about what we might do and the challenges of trying to reclaim some of this area. Now is called, the arts district. It’s a part of downtown now. No one recognizes this as Greenwood. How do you reclaim that? But then, this young women, she said, you know, “Well, I mean, we can try to reclaim it, but there are no black people down there now. All the black people, we’re all in north Tulsa. It’s like, I wish we could get this Greenwood art project thing in north Tulsa, where the black people are, because that’s where we stand to…” And so, that was really interesting for me to think about this. You have downtown and the old Greenwood area. And then, you have the north. But when I went on a tour with these young people, they took me all the way up, all the way up. And it’s a very interesting place. That’s where the people live and they have nothing. And they’re like, if you’re going to talk about the history of the Tulsa riot, that’s fine. That happened down near where the Greenwood Cultural Center is. But if you want to talk about Black Wall Street and going forward, our opportunity is up here. As we move through the project, part of it will be looking back at the history of it, but the other part is trying to look at, how do we recapture or create an opportunity for people to imagine themselves as rebuilding a Black Wall Street in the 21st century. Thank you.

STEPHANIE DOCKERY: Thank you so much for joining us. I think we’re all really curious how you came together and how your collaboration began?

JOHNSON: Well, I serve on the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission. The centennial comes up in 2021. And so, the idea behind the commission is to leverage the history to create the spirit of entrepreneurial activity that existed back then, and also to enhance the community such that people will be interested in visiting Greenwood as a cultural tourism site. So, that’s kind of what we’re doing. And I believe the city of Tulsa actually applied for the grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies, and of course the Centennial Commission is connected to the city, and there you go.

LOWE: Yeah, this guy who is also on the committee, contacted me and he said, we’re trying to have an art part to the centennial. He was saying he didn’t think that having just a sculpture, memorial sculpture, would be adequate for that. When he was telling me about it, in my memory of what I knew about the Tulsa riots, it was all about the destruction. To be quite honest, I’m so over that as black people, we’ve been beaten down so much and that story. I want something that’s much more empowering about what we can do, where we’re going, and not just laying in it.

So, I was like, I don’t know if I really want to do this, but he said, “Well, just come and visit.” So, I went to visit, and Hannibal, when I met with him, we had breakfast, and he just started talking about how the neighborhood came back. And I was like, what are you talking about? He was like, yeah, yeah. When I went on a tour in one of those buildings, the ones that still remain, and I looked at the top and it had 1922 on it. And I said, “Why is it 1922?” They said yeah, it was rebuilt. That was the most powerful thing of the visit for me was seeing and coming to terms with the fact that in 1921, terror hit that place and it just took everything down. But by 1922, someone had rebuilt. That’s the kind of spirit that I’m interested in.

DOCKERY: Much more inspiring dialogue. Interesting. And for Hannibal, Tulsa and Black Wall Street really exhibited a period of amazing economic growth for black Americans in the Jim Crow south. It echoed the success stories coming from Wall Street and what we know of post-industrial capitalism. And yet, the story is forgotten and the history is unknown. Why do you think, even within Oklahoma, this story is something that is not being spoken of?

JOHNSON: I think it’s complicated, like much of life. So, there are a lot of psychological dynamics going on.

There’s post-traumatic stress disorder that follows a traumatic event like that. There’s shame in many quarters of the white community. Tulsa, remember, is on a rapid upward trajectory at this point. So, Chamber of Commerce types want to minimize it. In fact, the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce, the Tulsa City Commission, the Tulsa Ministerial Alliance, they all refer to this as a Negro uprising. And it was their intention purposefully to minimize this to protect the image of Tulsa. In the black community, there was some degree of fear that this same sort of incident could recur. And if you couple that with the fact that this history is not included in curricular materials, so it doesn’t transmit over generations, we get to where we are today. I still run into people who are native to Tulsa who really don’t know anything about their own history. It’s amazing. Black people and white people.

DOCKERY: In speaking with the project team, they said that you will be partnering with local schools around Tulsa and the Tulsa Public School System to get the story back into the curriculum, or into the curriculum.

JOHNSON: Yeah, that’s one of the things that the Centennial Commission has focused on is working with the State Department of Education to create curriculum materials that make it easy for teachers to access this history teacher. Teachers are burdened with all manner of requirements these days. If you give them something that’s turnkey that they can access easily, they’re much more likely to engage with it.

DOCKERY: And Rick, you spoke at the announcement, and again here, about how you work within the concept of social sculpture devised by German artist Joseph Beuys. Can you talk about how you’ll bring that discipline to the Tulsa project?

LOWE: My thing about social sculpture and how to harness the creativity of local communities is extremely important to the work that I’m interested in, and particularly in a situation you know like this Tulsa situation. It just felt to me like there is something so deeply rooted for the people that are there that they need to tell that story. We have to figure out how to develop a platform for folks here to tell the story. Our goal is to mainly work with artists, at least the majority of the artists–from Oklahoma– really focusing on Tulsa in particular. And not to say that maybe there are going to be some artists that will come from other places or whatever, we don’t really know yet. But our big, big focus is going to be how do we connect folks within the Tulsa area? Which also means connecting the institutions.

All these different institutions around need to play a role. As I was talking to the young folks there the other day, a young group of African-American artists that call themselves Black Moon, we were talking about different things to do. And we started talking about some of the new things that are happening in the Greenwood district that people don’t really call Greenwood, like the baseball stadium. Apparently, at some point, they were using a name that, it was like the Brady baseball stadium. Some name that was not connected to the neighborhood. But we were talking about how great it would be that at the beginning of those baseball games that they actually had, like, these little films that would happen about Greenwood, about the place that they are, giving them opportunities to learn something about the place that they are. I’m excited about all of those kinds of institutions and places playing a role with the artists that we’re going to work with.

DOCKERY: The business community, the artists, the local non-profits, and the businesses that are still on Black Wall Street. What do both of you think we can learn from Black Wall Street and the history 100 years on, both the massacre and the success?

JOHNSON: For me, it’s all about the human spirit, as I said, and so it’s an inspirational story, ultimately. The tragedy is but one chapter in a much larger narrative, and the narrative is a story of the human spirit of a people. And so, we talk about the need for role models and such. We have plenty of role models. And also, I think it’s instructive in terms of the relativity of struggle or difficulty. If those people can do what they did against those tremendous odds, then why can’t we do more than what we’re doing now? That’s the message part of message for me.

LOWE: I started out by reading Hannibal’s book on Black Wall Street, which led me to deeper research. There’s incredible writings out there and research around the economic history of African-Americans since the Civil War. “The Color of Money.” It’s a great, great book that kind of looks at how African-Americans have been dealt with in the banking industry. There was another on, “Business in Black and White,” in terms of how different presidents have dealt with the African-American economic issue.

And what’s interesting about going into the history and researching broadly is to understand that this has been a journey for African-Americans. I mean, it’s been a long journey since coming to this country as slaves, but even after emancipation, of working inside and outside of official channels. What’s really informative to me about this is that every book that I’ve read, it talks about all these interesting things that have happened, from the Freedmen’s Bureau, all the way up to, the Nixon administration, basically. Certainly after the Carter administration, all reference to any need support and work with African-American communities to shore up its economic base just disappeared.

The narrative of black people since the late 1970s has been one of that “it’s our own fault.” For many different things, you know, drugs, violence, and all these things. There has been no policy that has been publicly championed around core issues of the problems within African-American communities – it’s that there’s no economic sustainability there. And so, I think that this centennial is going to be a great opportunity to push that to the forefront, and I’m hoping that the Greenwood Art Project will be at the forefront of that.

DOCKERY: Spaces in these communities have witnessed a tremendous amount of history. Looking at historical photos of Greenwood, and visiting today, it’s clear that the area has not significantly changed, even the cars are parked the same way. How are you both thinking about the role of public space?

LOWE: The project in Dallas, Trans.lation project, one of the interesting things about that place in terms of the space was that it was huge – I think something like 35,000 apartment units were in this concentrated area. It was designed in the 1970s around this notion of car culture independence where there weren’t bus stops, there weren’t sidewalks, there weren’t any of these things. It wasn’t designed for the way that the neighborhoods function now.

So, for us, trying to figure out how to put these little white cube galleries in, having some kind of public, became part of the strategy. You can see the challenge here, right? The way that the street grid has been taken away and in this university complex, which is way under-utilized. I think it was probably happening at a time when somebody could sell this idea to say like oh, we got to get rid of all of this poverty and dilapidation, and whatever, and we’re going to put universities there, and they’re going to do all this stuff. I mean, it’s just wasted space. So, it’s going to be really interesting for the city of Tulsa and we’re hoping that our project will give some guidance to that, of strategies and ways to start thinking about carving back into this place. Also, there’s an opportunity to reclaim some of this land from this university partnership because it’s under-utilized. And so, we’re hoping that we can start to do that.

DOCKERY: The grant cycle is for two years, but this project could have a longer life. And who knows what’s going to happen, especially in this participatory process. There are other projects that could last longer, as well. It’s temporary public art. But we’ll be supporting for two years, and it’ll be incredible to see what happens with the community and with Rick’s process, especially with the social sculpture that will start in the next couple of months.

JOHNSON: I always tell people that for me, when I’m doing projects in association with institutions – whether they’re museums, art institutions, or connected to funding cycles, if it’s successful, the best case scenario is that at the end point (or when the exhibition ends) is when the project begins. You know the ending is the beginning, right, because it’s utilizing the platform for me, utilizing the platform and exhibition to set the groundwork for something that can go, and move, and grow.

And similarly, with funding opportunities. You take the funding to be the catalyst for something that can actually move beyond. The other thing was for me, I was I was a little bit skeptical and Tulsa’s willingness to step up and really commit themselves to this, right? From the standpoint of dealing with it from a historical standpoint, but also dealing with it from the standpoint of how do you almost have some form of reparations or whatever? How do you invest in the future the idea of Black Wall Street? I was a little bit worried about that. But tell I have to say that the current mayor there now is a –

DOCKERY: Mayor Bynum.

JOHNSON: – pretty interesting guy. He’s pushing things in a very interesting way. Like, going back to actually look at the alleged burial grounds that are throughout the city. There have been people have been talking about that for a long time. And he is actually open to going back and looking at that.

I got a call to say, the mayor’s going to put together a bond package for the Greenwood neighborhood. How much money should he have in there for the art part? He wants this to be something that is really the center of what we do in in Greenwood going forward. So it’s already…the talk, it’s beginning to happen. They’re talking about it that way, which to me is very hopeful.

DOCKERY: Yes, Mayor Bynum has called tumultuous race relations a sin of our generation. So, he’s a huge advocate. I think there is a long life (for this project). I mean, with our inaugural Public Art Challenge, in Gary, Art House is still standing and serving the community. There have been numerous businesses that have evolved. So, if we can bring something to a community that is self-sustaining, that’s a really incredible legacy.

We have a long history of marginalized groups, immigrants and refugees being demonized. Can we alter that conversation and highlight the successes, doing better as a society moving forward – particularly using history or art?

JOHNSON: For me, it’s about curriculum. It’s about what we teach and how we teach it broadly. We have a tendency to sanitize our history. We don’t like to be uncomfortable. We don’t like to address issues that are systemic and complex. We prefer something superficial and simple, and we have to get beyond that. I think it’s a chronic challenge and I don’t think it’s ever going to fully abate. It’s always going to be a struggle for us to do what you suggest.

LOWE: Yeah. I mean, I agree with that. One of the reasons that I kind of promote and utilize this platform of social sculpture is that it’s really just trying to get people invested creatively in the process of being in a place that they are, because we’ve gotten very lazy. We are very lazy politically. We’re very lazy in terms of how we engage with our communities, with the places that we are. And so, I mean, to me, my hope is that it is through the opening up of the art process and inviting more creativity and engagement people that will kind of shift things a bit. And forcing them, because that creative engagement forces them to deal with those issues. For instance, the Tulsa thing right now, another thing that kind of scared me a little bit about Tulsa in the beginning, going there, was my first trip there, I was just Googling and reading some things, and I saw something about Oprah doing a television series on the 1921 massacre. And I read that and it was kind of interesting, but what was most interesting was to read the comments afterwards. And the comment section was just scary.

DOCKERY: You’ve got to get out of the comment section.

JOHNSON: Yeah.

LOWE: I mean, it was scary. And I’m always telling our committee and people that are meeting with them, saying, “You know what? You’re all great people, and it’s really good to hear you’re supportive, but you’re in a bubble because out there somewhere, people, they’re not only just trying to ignore it, they are aggressive against the real essence and meaning of that history. I think getting people engaged in the process of talking about it moves us forward.

JOHNSON: And the other thing I would add is that leadership matters. So, you talk about G.T. Byrum, our current mayor, his leadership matters enormously in terms of how this stuff evolves. Just as leadership matters at a national level. I’ll leave it at that.

DOCKERY: On that note, I just want to thank our guests so much for joining us.

OLIVER: We hope you enjoyed this episode of Follow the Data. Many thanks to Rick Lowe and Hannibal Johnson for joining us.

If you haven’t already, be sure to subscribe to Follow the Data podcast. This episode was produced by Electra Colevas, Stephanie Dockery and Rebecca Carriero, music by Mark Piro. Special thanks to Mark Siniscalchi.

As our founder Mike Bloomberg says, if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it. So until next time, keep following the data.

I’m Katherine Oliver, thanks for listening.